On 19 July 2024, a faulty update from widely used security software caused a global IT outage that disrupted government services, airlines, hospitals, and critical infrastructure across multiple countries. While investigators confirmed the event was accidental rather than malicious, the incident exposed a harsh reality: sensitive government workloads remain vulnerable when distributed across foreign-managed cloud platforms. Even without a cyberattack, the fragility of cross-border digital dependencies became undeniable.

For governments, digital sovereignty suddenly moved from a niche IT concern to a matter of national security doctrine. Managing data is no longer just about compliance; it is about defending strategic autonomy, preserving operational integrity, and safeguarding citizens’ trust. Digital infrastructure, once treated as an IT cost center, is now assessed with the same severity as military installations or energy grids.

At the heart of the tension lies a fundamental trade-off: the rapid innovation of global cloud services versus the control and accountability demanded by national security.

Sovereign data centers are no longer optional; they are a national priority.

Between Clouds and Control: Understanding Today’s Government Data Landscape

Today, many governments combine on-premises data centers for highly sensitive systems with commercial or hybrid cloud infrastructures for less sensitive workloads, a fragmented model meant to balance security with scalability. But this hybrid approach leaves an uneasy middle ground: data may still traverse foreign-managed infrastructure or be subject to foreign legal overlay when stored with global cloud services.

Under U.S. legislation such as the CLOUD Act, foreign cloud provider customers remain exposed; even if data is stored in Europe, U.S. authorities can compel access to data held by U.S.-based cloud providers. This has led to growing concern over “jurisdictional risk” when governments outsource critical workloads to major global providers.

As a reaction, leading cloud providers have begun offering “sovereign cloud” products tailored for public sector clients. For instance, Microsoft offers a “Sovereign Private Cloud” model with locally operated infrastructure, customer-managed encryption keys, and Azure-compatible services designed for disconnected or hybrid deployments.

Meanwhile, Google Cloud markets a “Sovereign Cloud” and “Distributed Cloud Hosted” offering with isolated infrastructure and partner-operated instances in Europe.

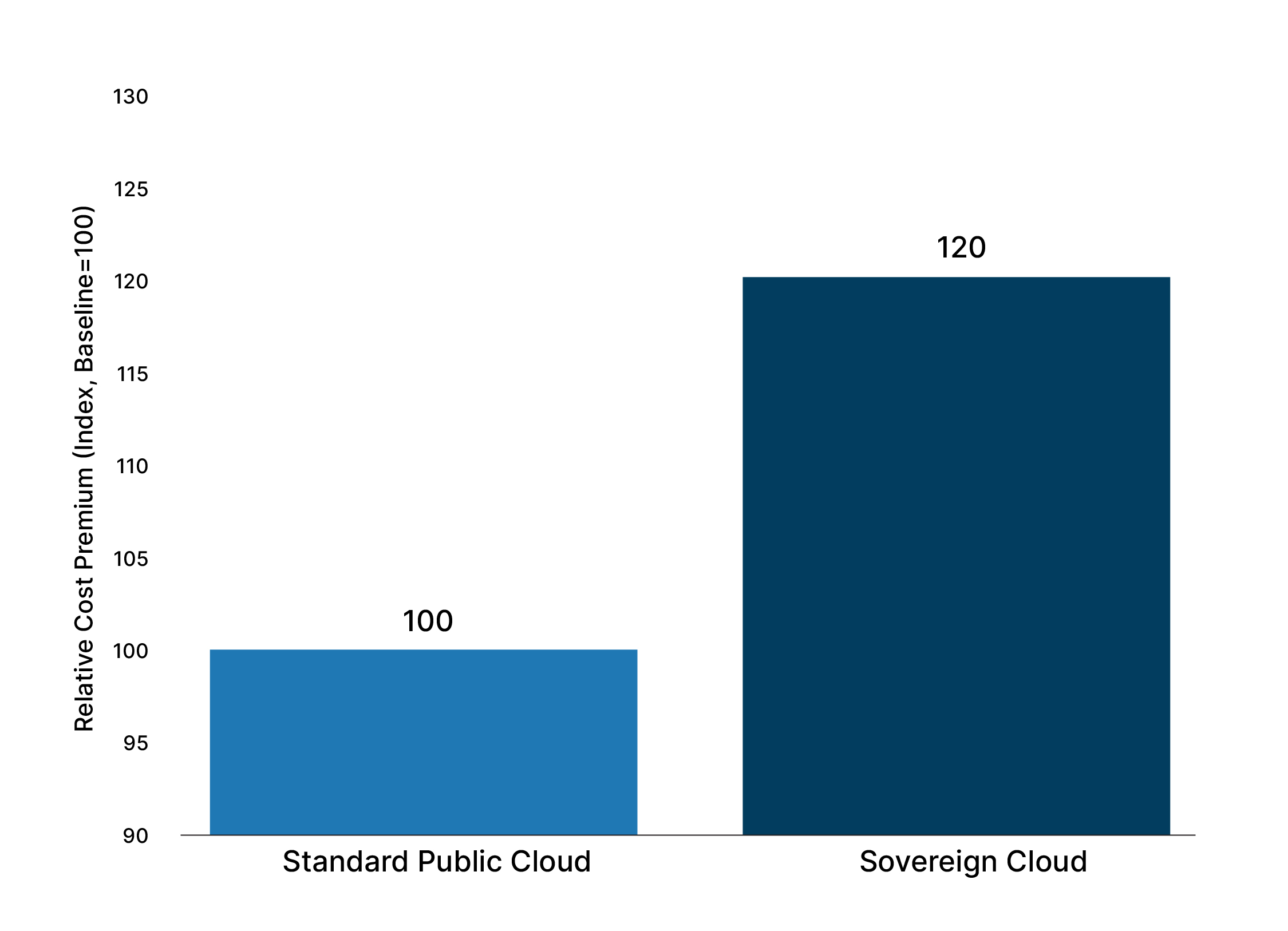

Yet challenges remain. Commercial cloud firms, even with “sovereign” labels, often deliver these services at a premium compared to standard public cloud pricing, which can constrain budget-conscious public sector clients.

Estimated Relative Cost Premium: Sovereign vs. Public Cloud

The Technologies Powering Sovereign Data Centers

Building sovereign data centers is no longer about placing racks inside a fenced compound; it is about assembling a stack of controls that together guarantee jurisdiction, accountability, and operational independence. The foundation begins with isolation. High-assurance zones are increasingly designed as logically separated or fully air-gapped environments, where traffic is constrained through one-way diodes or tightly governed gateways. NIST’s guidance on high-value asset protection notes that physical or logical separation remains one of the most reliable controls for limiting remote compromise in government systems.

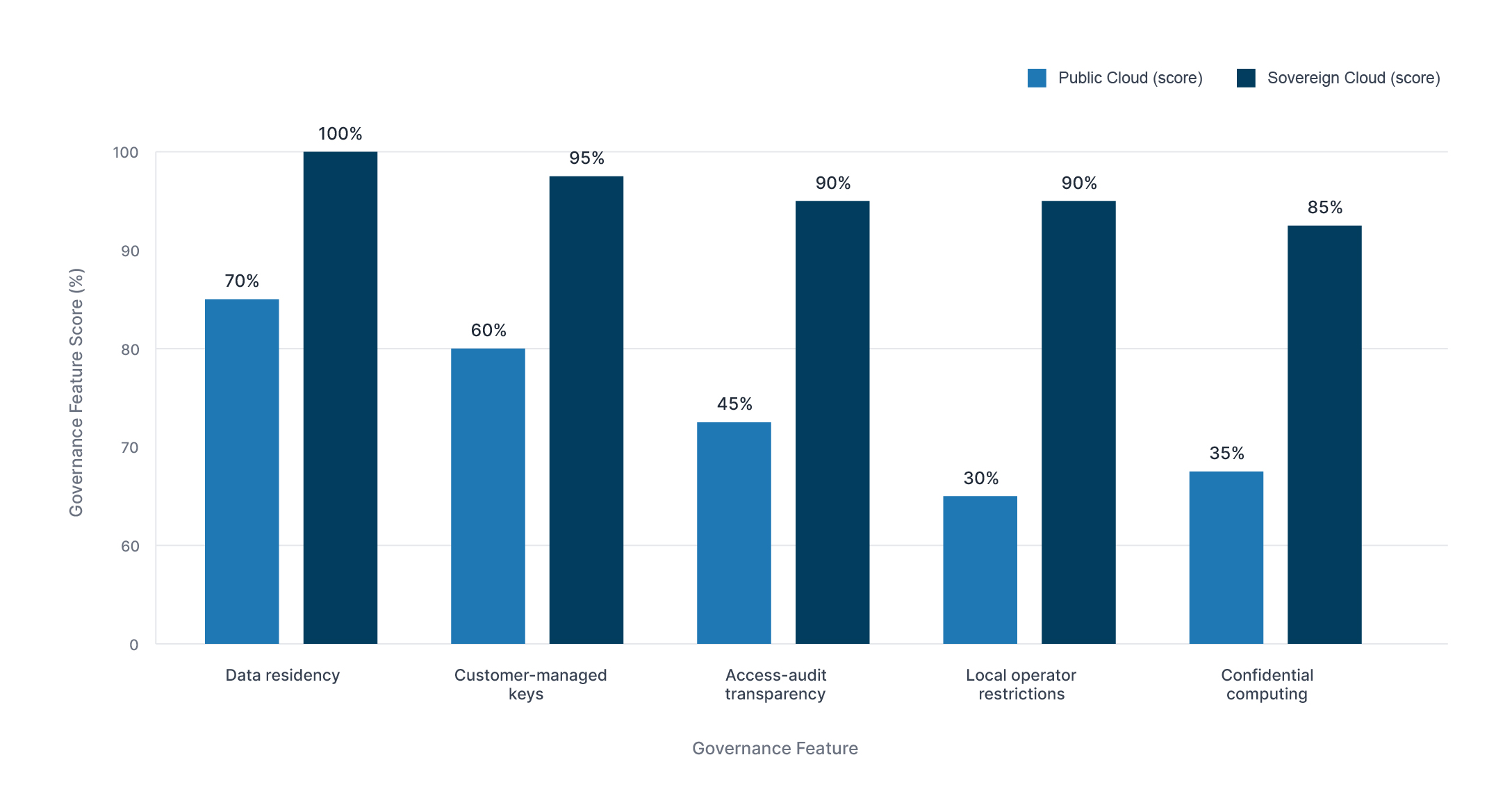

But modern sovereignty extends far beyond isolation. Governments are adopting confidential computing, where data remains encrypted even during processing, reducing reliance on operator trust.

Intel, AMD, and ARM all implemented enclave-based architectures, and the Confidential Computing

Hardware provenance is becoming a national-security requirement. Secure boot, attestation, and tamper-evident hardware, combined with country-approved vendors, allow agencies to validate every layer of the supply chain.

Sovereign Cloud vs Public Cloud: Governance Features Comparison Chart

This pairs with key sovereignty; governments increasingly demand exclusive control of encryption keys, even when workloads run on hyperscalers. ENISA’s cloud certification framework reinforces this, placing key management at the core of sovereignty assurance.

This pairs with key sovereignty; governments increasingly demand exclusive control of encryption keys, even when workloads run on hyperscalers. ENISA’s cloud certification framework reinforces this, placing key management at the core of sovereignty assurance.

Sovereign architectures also bring AI-ready infrastructure into the perimeter. GPU clusters for national-scale models, crime-intelligence workloads, and real-time infrastructure telemetry must operate inside national boundaries, monitored by unified SOC/NOC facilities that blend cyber, physical, and workload oversight.

Together, these innovations define a new blueprint: infrastructure that operates with cloud-like elasticity but under rules written by the state, not its vendors.

Who’s Defining the New Era of Sovereign Infrastructure

Sovereign infrastructure has moved from concept to execution. Microsoft’s Cloud for Sovereignty and its EU-focused commitments, including the EU Data Boundary rollouts and regional partnerships, have been positioned as a template for vendor-led sovereign offerings.

AWS has likewise published an overview and white papers describing its European Sovereign Cloud, arguing for an independently operated regional model backed by technical and legal assurances. Google’s Distributed Cloud Hosted (GDC Hosted), an air-gapped, partner-operated option, offers another pathway for governments that need strict residency and operational isolation.

Oracle has launched EU Sovereign Cloud regions and publicized early customer migrations to those regions, showing hyperscalers and established enterprise vendors competing for sovereign workloads.

National programs are growing in parallel. France’s Bleu (Capgemini + Orange) aims to provide a “cloud de confiance” under local control, while EU member states and telcos push national offers tailored to domestic regulation and procurement models.

The UAE and regional groups are moving fast, too; Microsoft’s investments and partnerships with G42 underscore how national-scale cloud capacity is increasingly part of state strategic plans. India continues to evolve its Digital India and MeitY-led cloud strategies to favor local capability and sovereign control.

Defense and allied programs add urgency. The U.S. Department of Defense’s Joint Warfighting Cloud Capability (JWCC) awards and related task orders show DoD is procuring commercial cloud capabilities under a sovereign-capable model. The UK MOD’s Digital Strategy and cloud roadmap explicitly prioritize classified and sovereign-capable cloud backbones.

NATO and allied bodies are similarly moving toward sovereign-grade arrangements, including recent partnership announcements for secure, air-gapped cloud capabilities.

What does the next decade demand?

If the last decade was about migrating to the cloud, the next will be about governing it. Sovereign cloud is not a defensive manoeuvre or a reaction to one outage; it is the beginning of a structural realignment in how states, operators, and hyperscalers negotiate control.

Governments are already shifting from “designing for peak” to “designing for unpredictability,” expecting systems to absorb failures, switch jurisdictions seamlessly, and maintain operability even when global platforms falter.

E-commerce and OTT providers have shown what happens when distributed systems are built to survive volatility; now national architectures are absorbing the same lessons. Edge nodes inside borders, confidential computing enclaves, and in-country AI accelerators will become the baseline for public services that cannot pause, reroute, or depend on foreign incident queues.

Ultimately, sovereign cloud marks the return of institutional confidence. Nations want agility without surrendering oversight and scale without diluting accountability.

The governments that thrive will be those that treat digital infrastructure not as procurement but as policy, an ongoing discipline of resilience, transparency, and strategic autonomy.

.jpg)