Mega-scale data center campuses were not designed for today’s thermal reality. What began as clusters of identical buildings cooled in isolation has evolved into dense, multi-building environments where heat no longer respects plot lines, phases, or original design assumptions.

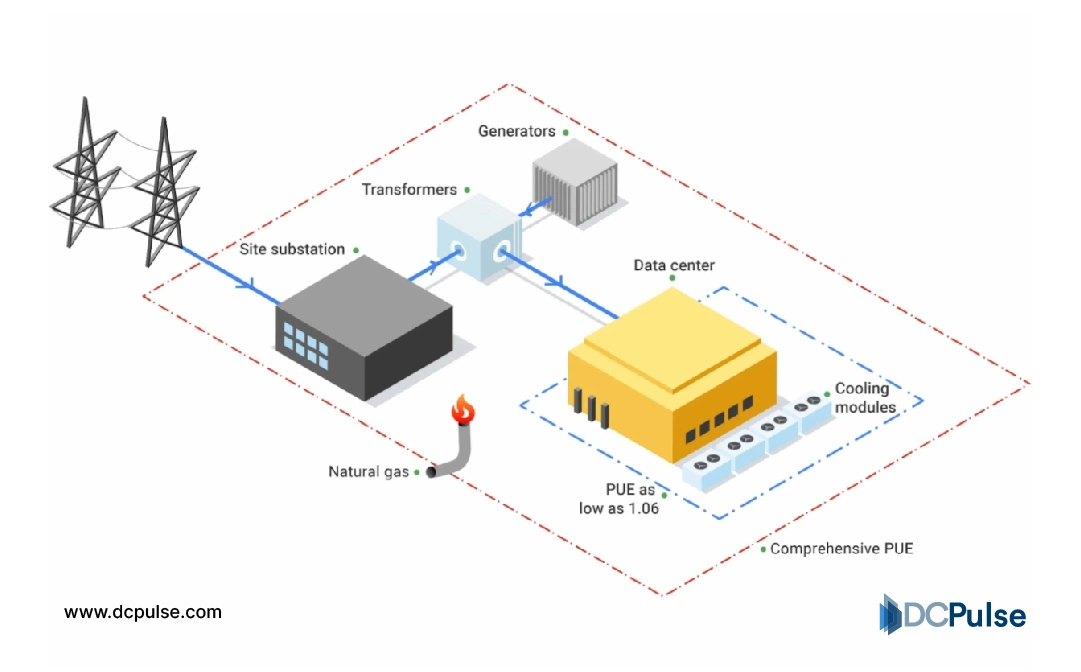

As power densities climb and AI workloads concentrate heat in new ways, cooling is no longer just a system inside a building. It has become a campus-wide design problem, shaped by land availability, phasing timelines, redundancy requirements, and how future capacity will be added without disrupting what is already live.

In this context, layout matters as much as technology. Where cooling plants sit, how loops are shared, how buildings connect, and how expansion zones are planned now influence efficiency, resilience, and cost at a scale individual halls never did.

The result is a quiet but consequential shift; cooling layouts are being rethought, not building by building, but as infrastructure that must work across an entire campus from day one and still make sense ten years later.

Cooling at Campus Scale: How Today’s Layouts Are Stretched to the Limit

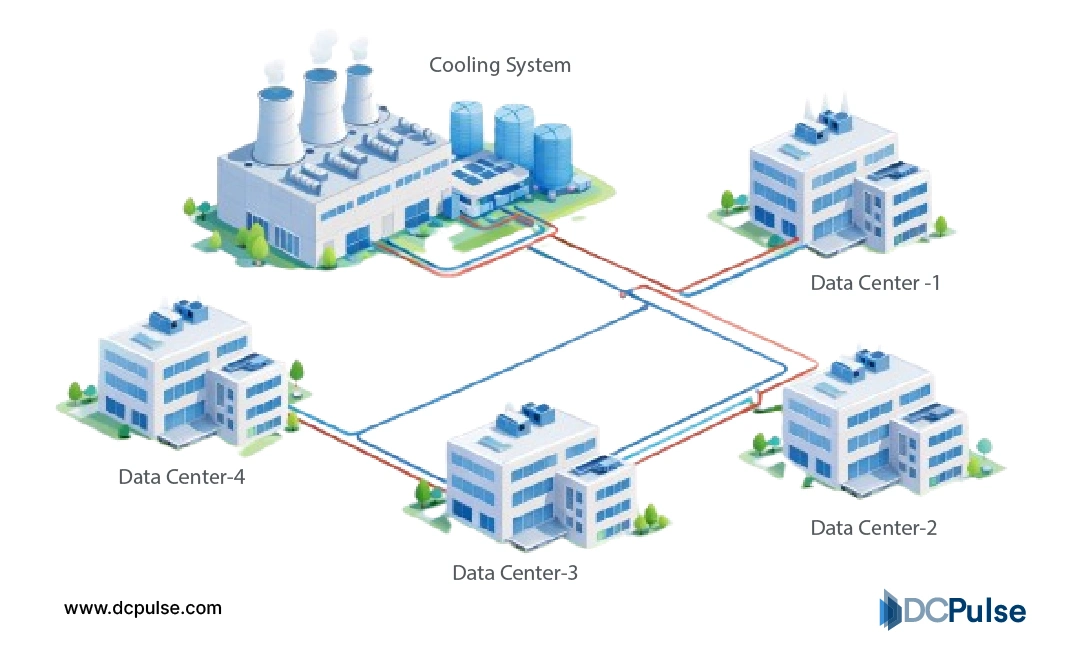

Most mega-scale data center campuses today rely on centralized cooling logic, even when the physical execution varies. Large chiller plants, cooling towers, or heat rejection systems are typically positioned to serve multiple buildings through shared distribution loops.

This approach delivers efficiency at scale, but it also assumes relatively uniform loads and predictable expansion paths, assumptions that are increasingly strained.

As operators add buildings in phases, cooling layouts must stretch across longer distances, cross active construction zones, and accommodate mixed generations of infrastructure. Industry guidance from ASHRAE highlights how distribution losses, pumping energy, and control complexity rise as chilled-water loops extend across large sites, making layout decisions as critical as equipment selection.

[Campus layout showing a centralized cooling plant feeding multiple data center buildings]

At the same time, density is becoming uneven across campuses. AI and accelerated workloads concentrate heat in specific buildings or halls, while others remain comparatively stable. Uptime Institute notes that this uneven load profile complicates traditional “one-size-fits-all” campus cooling designs, especially when redundancy is planned at both the building and campus level.

[Diagram comparing uniform-load campus cooling versus uneven, AI-driven density distribution]

![[Diagram comparing uniform-load campus cooling versus uneven, AI-driven density distribution]](../../..//uploads/images/Diagram_comparing_uniform-load_campus_cooling_versus_uneven,_AI-driven_density_distribution.webp)

Another constraint is operational isolation. While shared cooling improves efficiency, failures or maintenance events can ripple across multiple buildings if layouts are not carefully segmented. Operators increasingly balance shared infrastructure with isolation valves, looped headers, and partial decentralization to reduce blast radius, an approach reflected in large-campus design practices outlined by the U.S. Department of Energy.

Taken together, the current landscape shows why cooling layouts, not just cooling technology, are becoming a defining challenge for mega data center campuses.

Redrawing the Cooling Map: Layout Innovations Reshaping Mega Campuses

Cooling lay`outs for mega-scale data center campuses are being rethought at the planning stage, not retrofitted after density arrives. The most important shift is the move away from treating a campus as a single thermal system. Instead, operators are designing multiple cooling zones aligned to projected heat density, allowing different buildings, and even halls, to evolve independently.

One emerging layout innovation is the use of distributed cooling plants positioned closer to load clusters. By shortening chilled-water or condenser loops, campuses reduce pumping losses and improve fault isolation. Google has publicly detailed how its newer campuses rely on localized cooling systems tailored to individual buildings rather than oversized, site-wide plants, improving both efficiency and resilience as density varies across the site.

Another structural change is the separation of heat transport from heat rejection at the campus scale. Instead of locking the entire site into a single cooling method, operators are designing layouts where centralized heat rejection infrastructure supports multiple downstream cooling approaches. Meta’s engineering team has explained how this flexibility allows campuses to introduce liquid cooling in high-density zones without redesigning the broader cooling backbone

Campus planning itself is also evolving. Designers are now reserving physical corridors, plant footprints, and utility rights-of-way for future cooling expansion before construction begins. Campuses planned with future thermal zoning in mind are better able to scale AI workloads without disruptive retrofits.

Together, these layout-driven innovations reflect a clear reality: cooling is no longer a static utility layer; it is becoming a flexible framework that shapes how mega campuses grow.

How Cloud and Colocation Leaders Are Acting on New Cooling Layouts

As cooling layouts shift from centralized assumptions to flexible campus frameworks, major cloud and colocation operators are responding with structural decisions, not experiments. These moves are visible in how new campuses are planned, expanded, and marketed.

Google’s newer U.S. data center campuses reflect a clear departure from uniform site-wide cooling. The company has publicly outlined how individual buildings are increasingly designed with cooling systems matched to expected workloads, allowing newer halls to diverge from older ones without forcing a campus-wide redesign. This approach supports phased expansion while avoiding stranded cooling capacity as density evolves.

Meta’s campus strategy shows a similar shift, driven by AI workloads. In recent engineering disclosures, the company has described separating core campus infrastructure from building-level cooling decisions, enabling new AI-focused data halls to adopt liquid cooling without retrofitting adjacent facilities. This layout flexibility has become central to how Meta prepares campuses for rapid changes in compute intensity.

Colocation providers are also reshaping campus cooling layouts to remain competitive with hyperscalers. Uptime Institute research indicates that large multi-tenant campuses are increasingly designed with independent cooling domains per building or cluster, reducing shared risk and allowing operators to tailor cooling investments to tenant demand rather than enforcing a single campus standard.

Taken together, these moves show that cooling layout decisions are now tied directly to competitive positioning. Operators that can adapt campus cooling faster are better positioned to absorb AI growth without slowing expansion.

Cooling Layouts as Long-Term Campus Strategy

Cooling layouts are no longer just an engineering outcome of campus growth; they are becoming a strategic input into how cloud and colocation operators plan scale. As mega campuses expand unevenly, the ability to adapt cooling infrastructure without disrupting live operations is emerging as a quiet differentiator.

One clear takeaway is that layout flexibility now matters more than peak efficiency. Operators are prioritizing designs that allow buildings, halls, and clusters to evolve independently, even if that means moving away from perfectly optimized centralized systems. This reflects a broader industry acceptance that density will arrive unevenly, driven by AI workloads that defy traditional planning assumptions.

Another implication is financial. Cooling layouts that support phased deployment help avoid stranded capital, especially in campuses built years ahead of demand. Research from the Uptime Institute consistently shows that overbuilt cooling infrastructure is a leading source of inefficiency in large facilities, reinforcing the shift toward modular, expandable campus designs.

Looking ahead, the campuses that scale fastest will not be those with the most advanced cooling technology, but those with layouts designed to absorb change, new densities, new cooling methods, and new operational constraints without forcing wholesale redesigns. In that sense, cooling layout decisions made today are quietly shaping the pace of cloud expansion for the next decade.